The Life of Siddhartha Guatama

The Life of Siddhartha Gautama

Dr. C. George Boeree

Shippensburg University

There was a small country in what is now southern Nepal that was ruled by a clan called the Shakyas. The head of this clan, and the king of this country, was named Shuddodana Gautama, and his wife was the beautiful Mahamaya. Mahamaya was expecting her first born. She had had a strange dream in which a baby elephant had blessed her with his trunk, which was understood to be a very auspicious sign to say the least.

As was the custom of the day, when the time came near for Queen Mahamaya to have her child, she traveled to her father's kingdom for the birth. But during the long journey, her birth pains began. In the small town of Lumbini, she asked her handmaidens to assist her to a nearby grove of trees for privacy. One large tree lowered a branch to her to serve as a support for her delivery. They say the birth was nearly painless, even though the child had to be delivered from her side. After, a gentle rain fell on the mother and the child to cleanse them.

It is said that the child was born fully awake. He could speak, and told his mother he had come to free all mankind from suffering. He could stand, and he walked a short distance in each of the four directions. Lotus blossoms rose in his footsteps. They named him Siddhartha, which means "he who has attained his goals." Sadly, Mahamaya died only seven days after the birth. After that Siddhartha was raised by his mother’s kind sister, Mahaprajapati.

King Shuddodana consulted Asita, a well-known sooth-sayer, concerning the future of his son. Asita proclaimed that he would be one of two things: He could become a great king, even an emperor. Or he could become a great sage and savior of humanity. The king, eager that his son should become a king like himself, was determined to shield the child from anything that might result in him taking up the religious life. And so Siddhartha was kept in one or another of their three palaces, and was prevented from experiencing much of what ordinary folk might consider quite commonplace. He was not permitted to see the elderly, the sickly, the dead, or anyone who had dedicated themselves to spiritual practices. Only beauty and health surrounded Siddhartha.

Siddhartha grew up to be a strong and handsome young man. As a prince of the warrior caste, he trained in the arts of war. When it came time for him to marry, he won the hand of a beautiful princess of a neighboring kingdom by besting all competitors at a variety of sports. Yashodhara was her name, and they married when both were 16 years old.

As Siddhartha continued living in the luxury of his palaces, he grew increasing restless and curious about the world beyond the palace walls. He finally demanded that he be permitted to see his people and his lands. The king carefully arranged that Siddhartha should still not see the kind of suffering that he feared would lead him to a religious life, and decried that only young and healthy people should greet the prince.

As he was lead through Kapilavatthu, the capital, he chanced to see a couple of old men who had accidentally wandered near the parade route. Amazed and confused, he chased after them to find out what they were. Then he came across some people who were severely ill. And finally, he came across a funeral ceremony by the side of a river, and for the first time in his life saw death. He asked his friend and squire Chandaka the meaning of all these things, and Chandaka informed him of the simple truths that Siddhartha should have known all along: That all of us get old, sick, and eventually die.

Siddhartha also saw an ascetic, a monk who had renounced all the pleasures of the flesh. The peaceful look on the monks face would stay with Siddhartha for a long time to come. Later, he would say this about that time:

When ignorant people see someone who is old, they are disgusted and horrified, even though they too will be old some day. I thought to myself: I don’t want to be like the ignorant people. After that, I couldn’t feel the usual intoxication with youth anymore.

When ignorant people see someone who is sick, they are disgusted and horrified, even though they too will be sick some day. I thought to myself: I don’t want to be like the ignorant people. After that, I couldn’t feel the usual intoxication with health anymore.

When ignorant people see someone who is dead, they are disgusted and horrified, even thought they too will be dead some day. I thought to myself: I don’t want to be like the ignorant people. After than, I couldn’t feel the usual intoxication with life anymore. (AN III.39, interpreted)

At the age of 29, Siddhartha came to realize that he could not be happy living as he had been. He had discovered suffering, and wanted more than anything to discover how one might overcome suffering. After kissing his sleeping wife and newborn son Rahula goodbye, he snuck out of the palace with his squire Chandara and his favorite horse Kanthaka. He gave away his rich clothing, cut his long hair, and gave the horse to Chandara and told him to return to the palace. He studied for a while with two famous gurus of the day, but found their practices lacking.

He then began to practice the austerities and self-mortifications practiced by a group of five ascetics. For six years, he practiced. The sincerity and intensity of his practice were so astounding that, before long, the five ascetics became followers of Siddhartha. But the answers to his questions were not forthcoming. He redoubled his efforts, refusing food and water, until he was in a state of near death.

One day, a peasant girl named Sujata saw this starving monk and took pity on him. She begged him to eat some of her milk-rice. Siddhartha then realized that these extreme practices were leading him nowhere, that in fact it might be better to find some middle way between the extremes of the life of luxury and the life of self-mortification. So he ate, and drank, and bathed in the river. The five ascetics saw him and concluded that Siddhartha had given up the ascetic life and taken to the ways of the flesh, and left him.

In the town of Bodh Gaya, Siddhartha decided that he would sit under a certain fig tree as long as it would take for the answers to the problem of suffering to come. He sat there for many days, first in deep concentration to clear his mind of all distractions, then in mindfulness meditation, opening himself up to the truth. He began, they say, to recall all his previous lives, and to see everything that was going on in the entire universe. On the full moon of May, with the rising of the morning star, Siddhartha finally understood the answer to the question of suffering and became the Buddha, which means “he who is awake.”

It is said that Mara, the evil one, tried to prevent this great occurrence. He first tried to frighten Siddhartha with storms and armies of demons. Siddhartha remained completely calm. Then he sent his three beautiful daughters to tempt him, again to no avail. Finally, he tried to ensnare Siddhartha in his own ego by appealing to his pride. That, too, failed. Siddhartha, having conquered all temptations, touched the ground with one hand and asked the earth to be his witness.

Siddhartha, now the Buddha, remained seated under the tree -- which we call the bodhi tree -- for many days longer. It seemed to him that this knowledge he had gained was far too difficult to communicate to others. Legend has it that Brahma, king of the gods, convinced Buddha to teach, saying that some of us perhaps have only a little dirt in our eyes and could awaken if we only heard his story. Buddha agreed to teach.

At Sarnath near Benares, about one hundred miles from Bodh Gaya, he came across the five ascetics he had practiced with for so long. There, in a deer park, he preached his first sermon, which is called “setting the wheel of the teaching in motion.” He explained to them the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path. They became his very first disciples and the beginnings of the Sangha or community of monks.

King Bimbisara of Magadha, having heard Buddha’s words, granted him a monastery near Rahagriha, his capital, for use during the rainy season. This and other generous donations permitted the community of converts to continue their practice throughout the years, and gave many more people an opportunity to hear the teachings of the Buddha.

Over time, he was approached by members of his family, including his wife, son, father, and aunt. His son became a monk and is particularly remembered in a sutra based on a conversation between father and son on the dangers of lying. His father became a lay follower. Because he was saddened by the departures of his son and grandson into the monastic life, he asked Buddha to make it a rule that a man must have the permission of his parents to become a monk. Buddha obliged him.

His aunt and wife asked to be permitted into the Sangha, which was originally composed only of men. The culture of the time ranked women far below men in importance, and at first it seemed that permitting women to enter the community would weaken it. But the Buddha relented, and his aunt and wife became the first Buddhist nuns.

The Buddha said that it didn’t matter what a person’s status in the world was, or what their background or wealth or nationality might be. All were capable of enlightenment, and all were welcome into the Sangha. The first ordained Buddhist monk, Upali, had been a barber, yet he was ranked higher than monks who had been kings, only because he had taken his vows earlier than they!

Buddha’s life wasn’t without disappointments. His cousin, Devadatta, was an ambitious man. As a convert and monk, he felt that he should have greater power in the Sangha. He managed to influence quite a few monks with a call to a return to extreme asceticism. Eventually, he conspired with a local king to have the Buddha killed and to take over the Buddhist community. Of course, he failed.

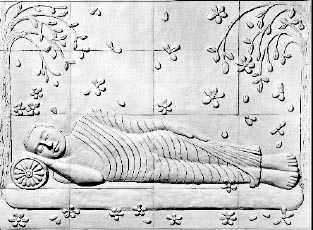

Buddha had achieved his enlightenment at the age of 35. He would teach throughout northeast India for another 45 years. When the Buddha was 80 years old, he told his friend and cousin Ananda that he would be leaving them soon. And so it came to be that in Kushinagara, not a hundred miles from his homeland, he ate some spoiled food and became very ill. He went into a deep meditation under a grove of sala trees and died. His last words were...

Impermanent are all created things;

Strive on with awareness.